(This is an archived old post from the previous version of the page.)

We have the first hour of the game in very much playable shape, so we figured it’s the right moment to playtest it. What’s “the right moment”? Why are playtests important?

Antichamber made five million dollars for its creator, with 750K copies sold. In this presentation, you can hear about various reasons behind this success story, and playtesting was one of the major ones. The game never really changed its soul and core idea, but observing how it changed the form because of the playtests is fascinating.

There’s this myth that if the creator – the artist! – consults other people on their work then that’s degrading and kills the soul, both of the creator and the creation. That’s just silly. Think about it this way: do great actors know their craft? Obviously, duh! – right? Why do they need a director, then?

And with games the participation of outsiders in the creative process is even more important, as games are interactive entities. It’s very hard to make a movie that sustains the interest of the viewer the entire time and hits all the right spots at all the right moments. And we’re talking linear, passive experience here. Games are neither linear (even the linear ones) nor passive. The room for error, be it UI or pacing, is much greater.

However, if you still have doubts about your design tainted by the outsiders, just remember this:

“Remember: when people tell you something’s wrong or doesn’t work for them, they are almost always right. When they tell you exactly what they think is wrong and how to fix it, they are almost always wrong.” — Neil Gaiman

In other words, playtester’s job is mostly to let you know what went wrong and right with your game. Their job is not to fix the problems for you – even if they want to. All conclusions, all action items, all tweaks and improvements and updates – that’s entirely on you. Including the decision if you even agree that the reported problems are really problems in the first place.

Here’s an example from the playtest of our game, one that we held earlier this month. All players mentioned that initially they did not understand a certain feature (it is a very small one, but indeed something I had not seen in games before), and they realized what it does and how to deal with it only a bit later in the game.

“Great!” – I said. “It’s a game about exploration and discovery, and you all managed to solve the problem entirely on your own. We’re not changing anything here, then.”

Obviously, there’s no guarantee that I’m right. The point is: it’s up to the creators to dig deep into the true meaning of the feedback.

Another thing – and a big problem – with playtests is that they are biased and corrupt by default. For example, if someone is asked to playtest a game, they believe they have to give feedback – so their evaluation of the experience is different to the one they would have if they played the game at home.

The list goes on and on: people might be biased towards your game just because they feel special getting the invitation to see something not many have seen before them, or people might be too harsh, because their experience is influenced negatively by the fact they’re being watched. And so on, and so forth.

But it all does not matter that much. Any playtest is better than no playtest at all.

Finally, before we talk more about the actual playtests of Ethan, another thing to remember is the prioritization of the feedback. I’m not talking about bugs versus enhancements or pacing versus understanding of the story. I’m talking about what David Jaffe said once about playtester scores.

I cannot find the source on the net – my Google-fu is not strong today, apparently – so let me just quote David from memory. He said that when they playtested a game (was it the latest Twisted Metal?) he kind of put all review cards with 9/10s and 10/10s to the bottom of the pile, because “we already got these guys.” He also dismissed all very low scores like 4/10, as they meant that either the playtester hated the genre, or the game was simply beyond repair for them, especially given the time to release.

So, his focus became all the 7/10s and 8/10s entirely. Because these are the people that want to like the game, and, more importantly, can like the game; it’s just that something is stopping them from doing just that. And these are the problems to solve in the first place. Elevating the player score from 7/10 to 8/10 or from 8/10 to 9/10 is not easy, but that’s exactly what game developers should (and usually do) focus on around alpha.

So, with all these things in mind, a few bits of info on how the playtest of Ethan Carter went. We have invited ten gamedev friends from various Polish studios, as these guys see through the noise (some placeholder assets, bugs, etc.) a bit easier than regular gamers.

The best thing about the playtest was that everyone declared they would want to continue playing, curious about “what happens next”. Other good words were passed around too. Our goal was to learn if we wasted the last two years of our lives with this risky game, and it seems like we didn’t. Of course, there’s a lot of work still to be done: but it’s about tweaking and improving, not about re-designing.

Let me mention three other important findings…

ONE THING THAT WENT RIGHT

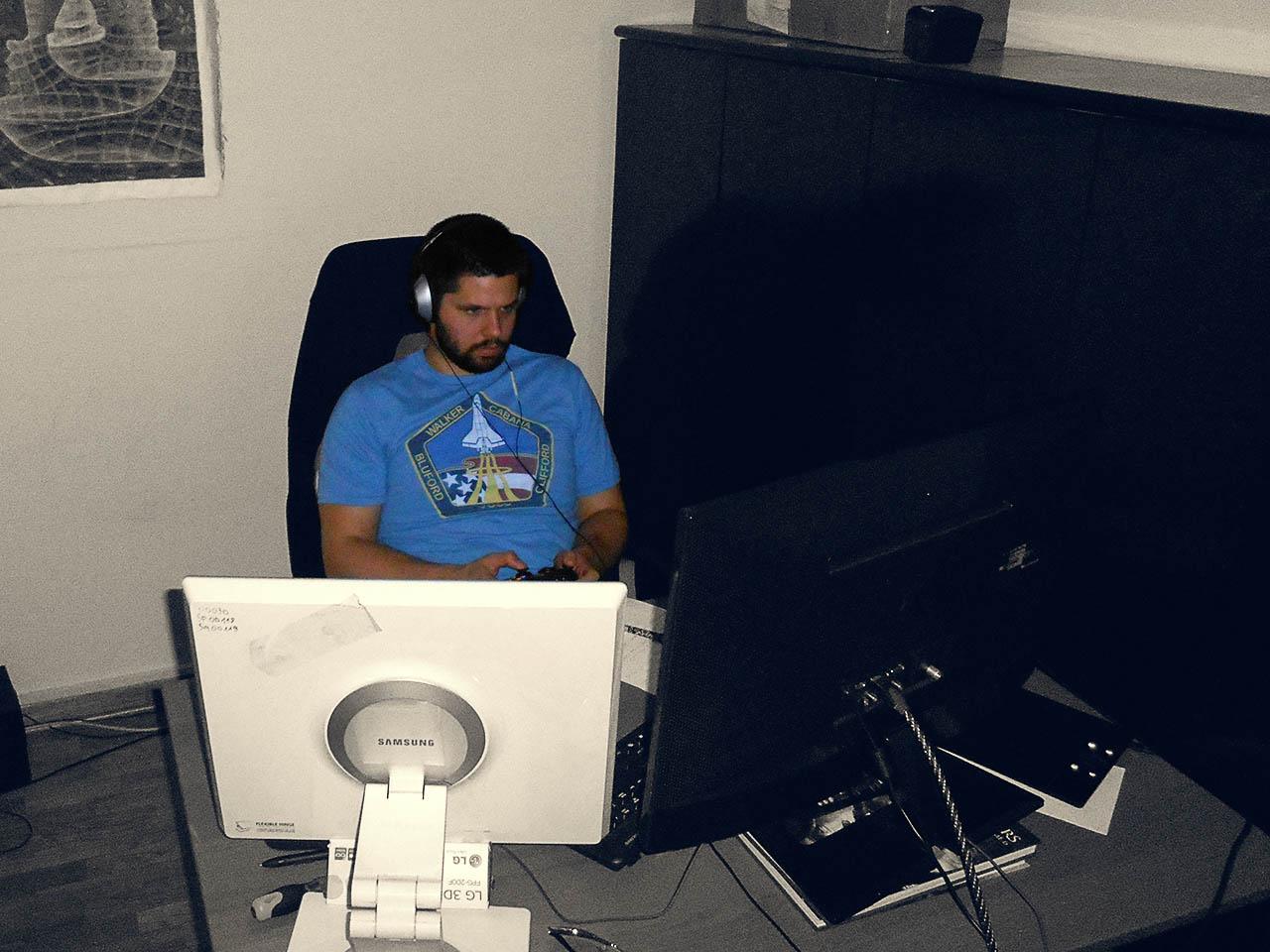

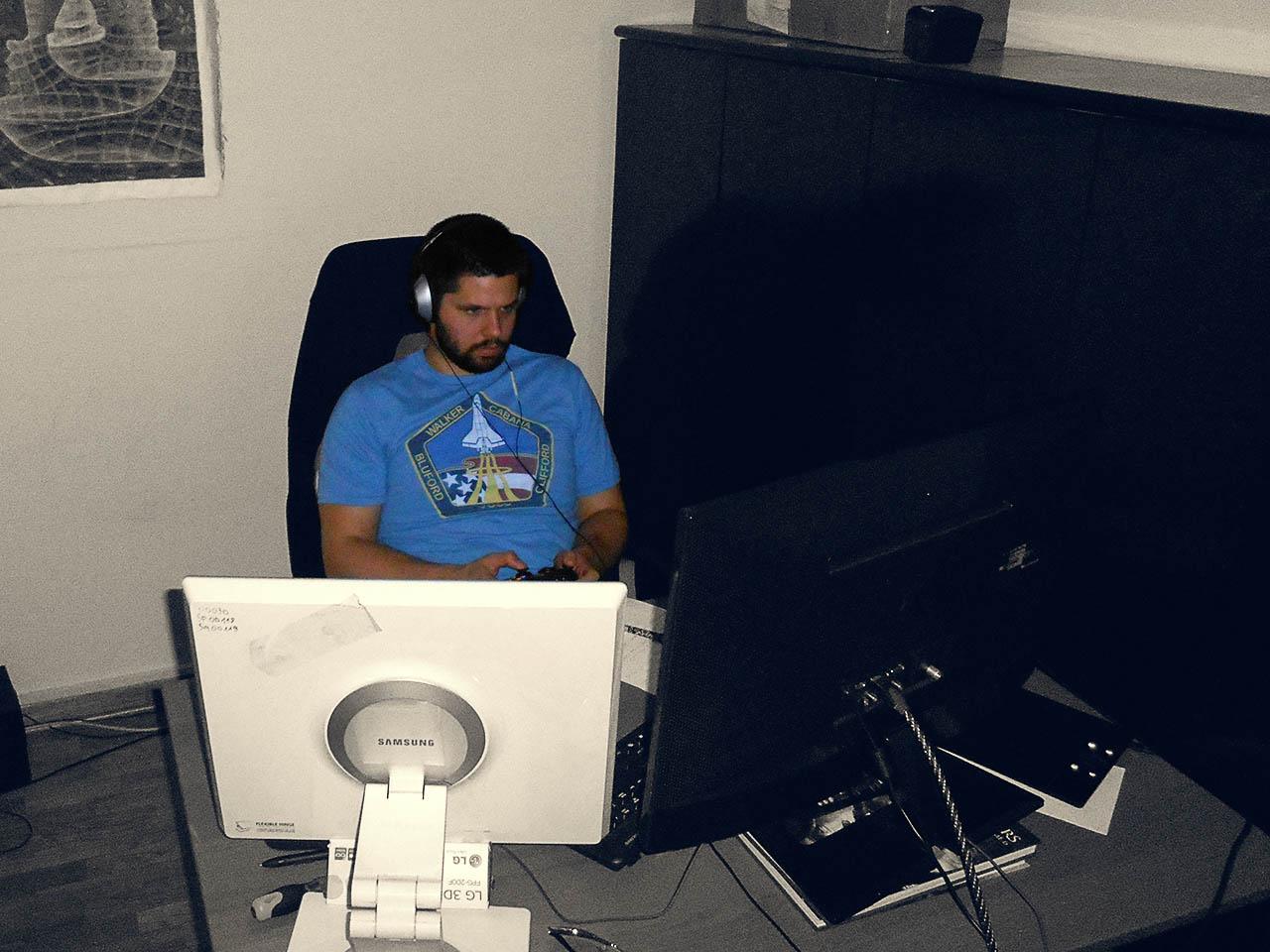

We have decided against recording or sitting next to the players. Ethan is a game to savor and not rush through under the curious eyes of the creators. So the feedback came mostly from the talks after the playthrough and from the questionnaire we asked the devs to fill in later through e-mail. We chose that solution on purpose, as wanted people to write only about what they really remembered as good or bad, and not about every little thing they might have considered a problem during the play (to somewhat neutralize the natural corruption of playtests).

ONE THING THAT WENT WRONG

Bugs. First, we had incorrectly playtested the game ourselves before we had our guests play it. We have checked every little thing, but in a linear order. But that’s not how people played the game. They sampled an area, did a few things, moved on to another area, then eventually came back later. That’s cool, this is part of the core design – but we just did not play the game this way ourselves: it’s hard to drop an activity (like figuring out what happened at the murder scene) in the middle of it when you know exactly how to finish it.

Second, one nasty and crazy bug – crouching caused the mist to appear on the entire level… Don’t ask… – ruined a lot of playthroughs. We had to reset the game or spoil a part of it in order to make the bug disappear.

ONE THING THAT WAS UNEXPECTED

Actually, the same thing as I mentioned above: players enjoying the game in a non-linear fashion. I am not a player like that. I scan every square centimeter and only move forward if I know I have “exhausted” the area. But almost everybody at the playtest did a few things in one area, then moved to another, and came back, or maybe not, maybe went to yet another area instead, etc. And people seemed to enjoy that freedom.

I remember some team members asking me “Why are we doing this playtest? What do you want to learn from this?”. And I always answered: “I don’t know. I really don’t. But I know we will definitely learn something.” And that turned out to be 100% true. The feedback – apart from discovering problems we would have never spotted ourselves – inspired a few cool small improvements as well.

Thanks again to our friends for their help, and here’s to the next playtest soon.