(This is an archived old post from the previous version of the page.)

How did a small FMV game become Gamespot’s Game of the Month? Is it a “feminist propaganda”? Is it even a game? And why is it so good when it makes no sense?

I mostly want to address the first and the last question, but there’s no escaping the middle two: they are, sadly, a part of the online discussion about Her Story. Let’s just address them first, then, clear the air, and open the way for an uninterrupted design analysis – spoiler-free! – of the game.

My essays on game design on this official studio’s website rarely touch the sociopolitical aspects of gaming. I do that on my private Medium blog. I am making a small exception this time because we cannot escape the sociopolitics when we talk about Her Story. Why?

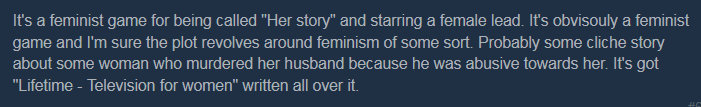

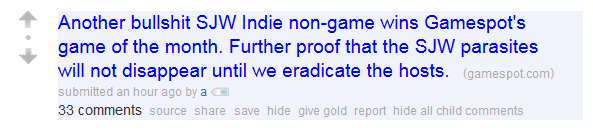

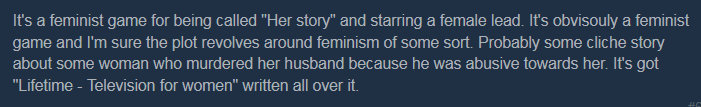

Take a look at this post on the game’s Steam forum:

Or this one on Reddit:

Now, it would be easy to laugh at the tin foil rage of these posts. Actually, go ahead and do just that, I’ll wait.

To be fair, basically everyone else in these communities quickly jumped in and disagreed with the posters, in writing or through vigorous downvoting. That is important to acknowledge, I believe.

However, it would be a mistake to think these comments are something I merely cherry-picked to manufacture a controversy. “It’s not a game” and “it’s a feminist propaganda” are accusations that do not dominate the discourse — luckily, far from that! — but I see them often enough to not dismiss them as random glitches in the matrix.

Now, we could – and should – see beyond the hate veil and ask ourselves: why exactly did these two guys – and quite a few others – feel the need to viciously attack the game from the “not a game” and “propaganda” angle?

I could attempt to answer that. We could try to figure out why some gamers have become so defensive, hyper-sensitive and mistrustful. I happen to believe we could find reasons, and I could list those reasons and make a connection between the smoke and the fire.

But, as I said it earlier, it’s not this kind of blog. Not answering this question is also much easier thanks to the following simple fact:

Her Story is not a “feminist propaganda”, and it is a game.

I’ll talk about what is and what is not a game in a second, but let’s deal with the propaganda first.

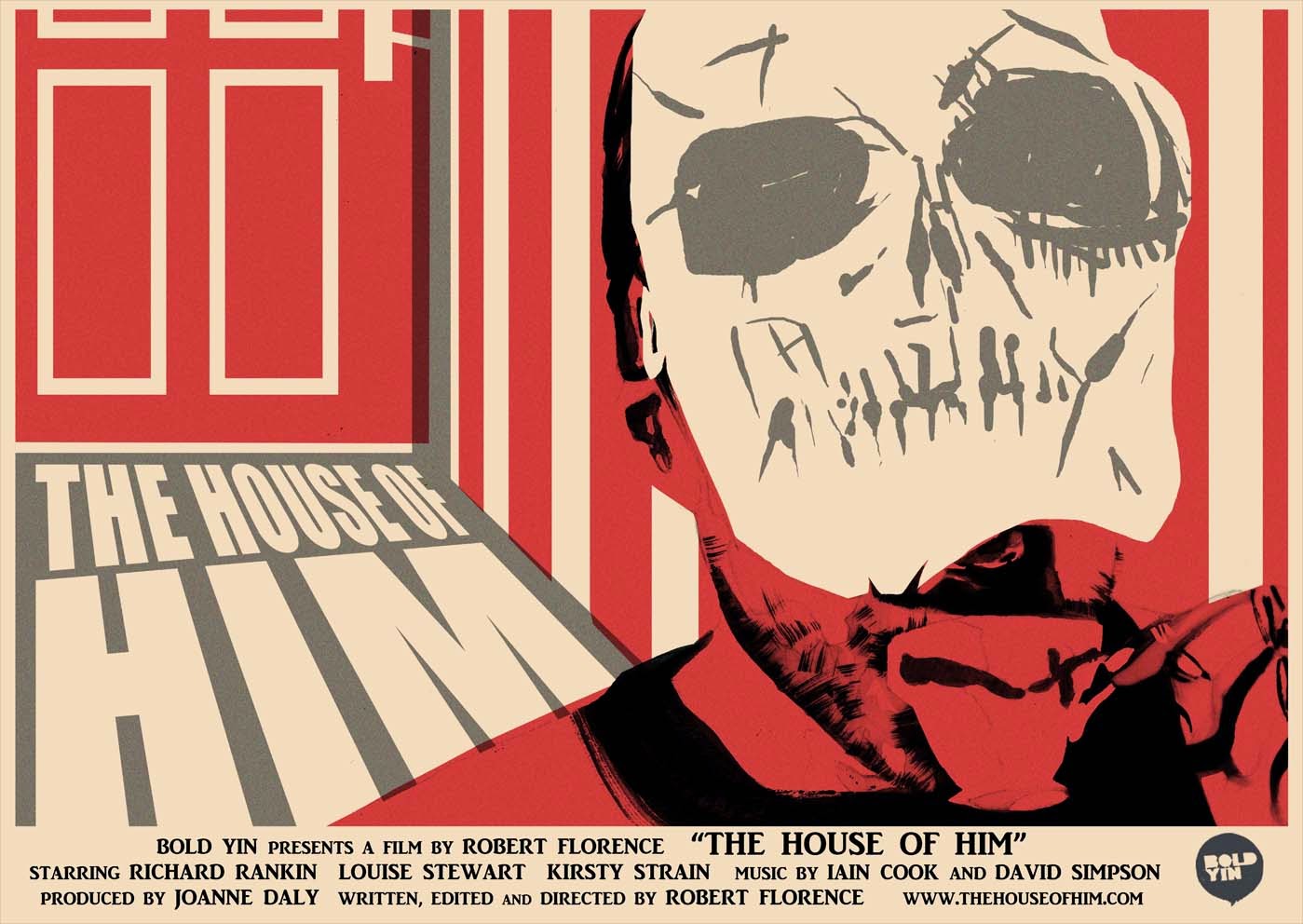

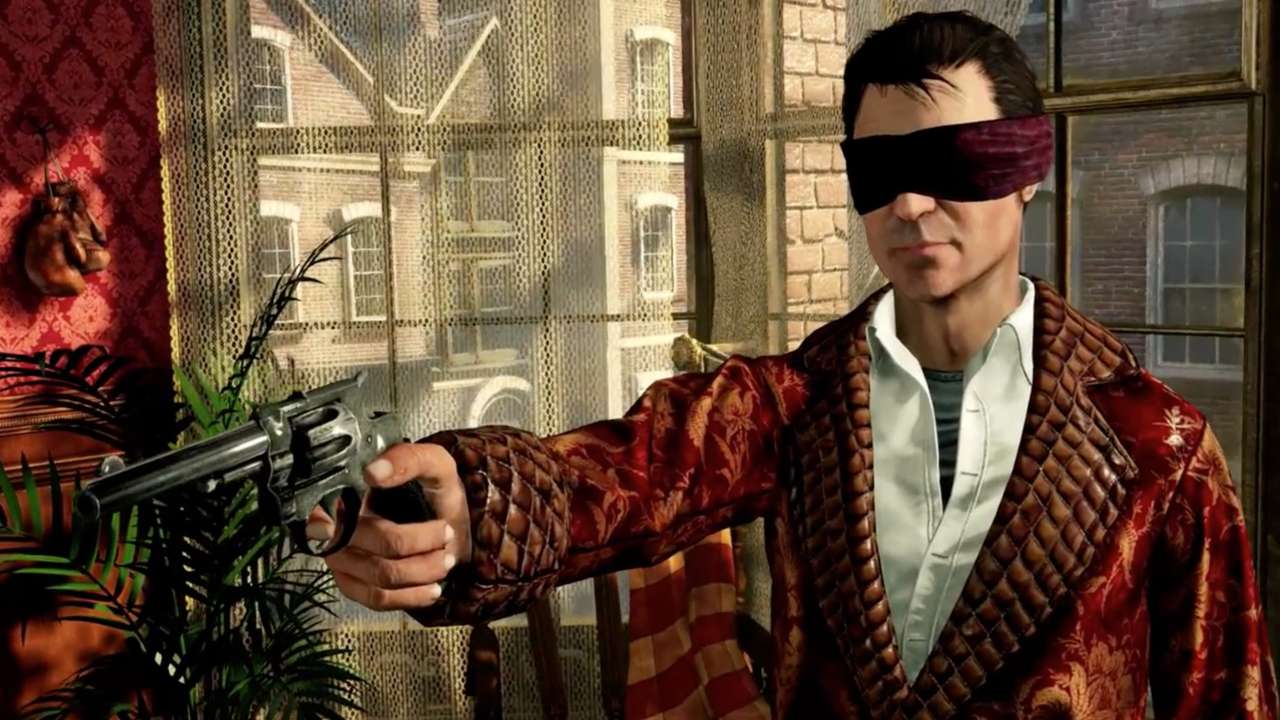

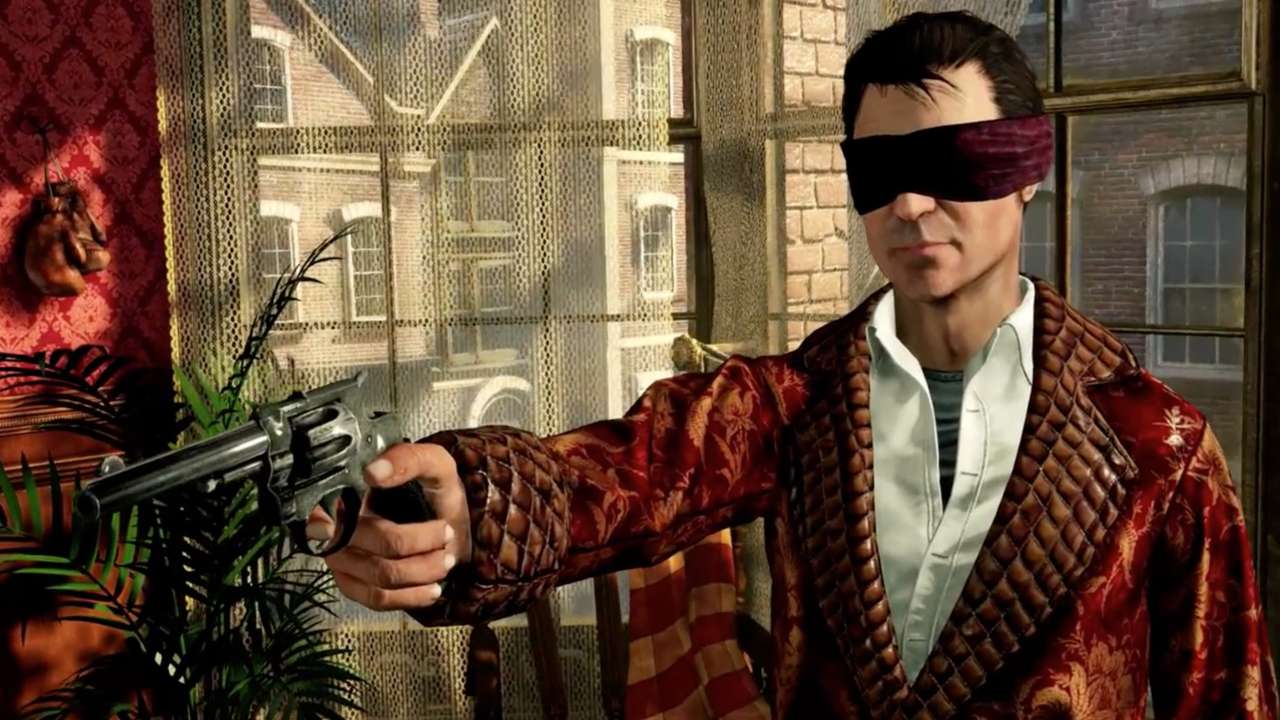

Sam Barlow, the lead designer and writer of the excellent Silent Hill: Shattered Memories, and the creator of Her Story, had a little fun with this accusation:

In case you don’t get the joke – and I don’t blame you, since not many people have seen The House of Him – it’s an equivalent of saying “Scared off of Super Mario 3D World because you heard rumors of an excessive violence? Go watch Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom — it’s just a fun little relaxing movie”.

Personally, I might not mind if Her Story was propaganda, assuming it was well written and well executed, or that it at least had some thought-provoking moments or ideas.

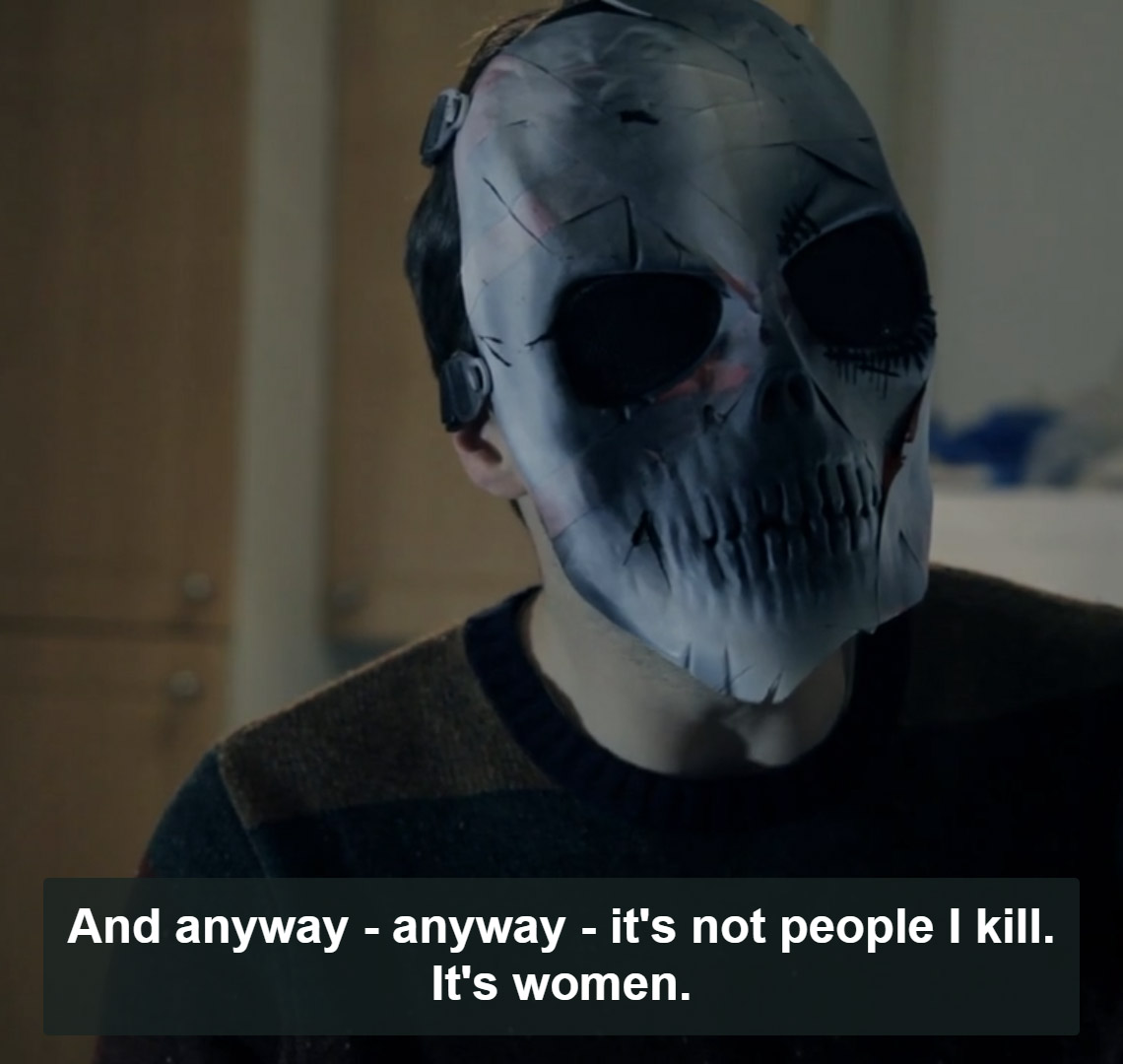

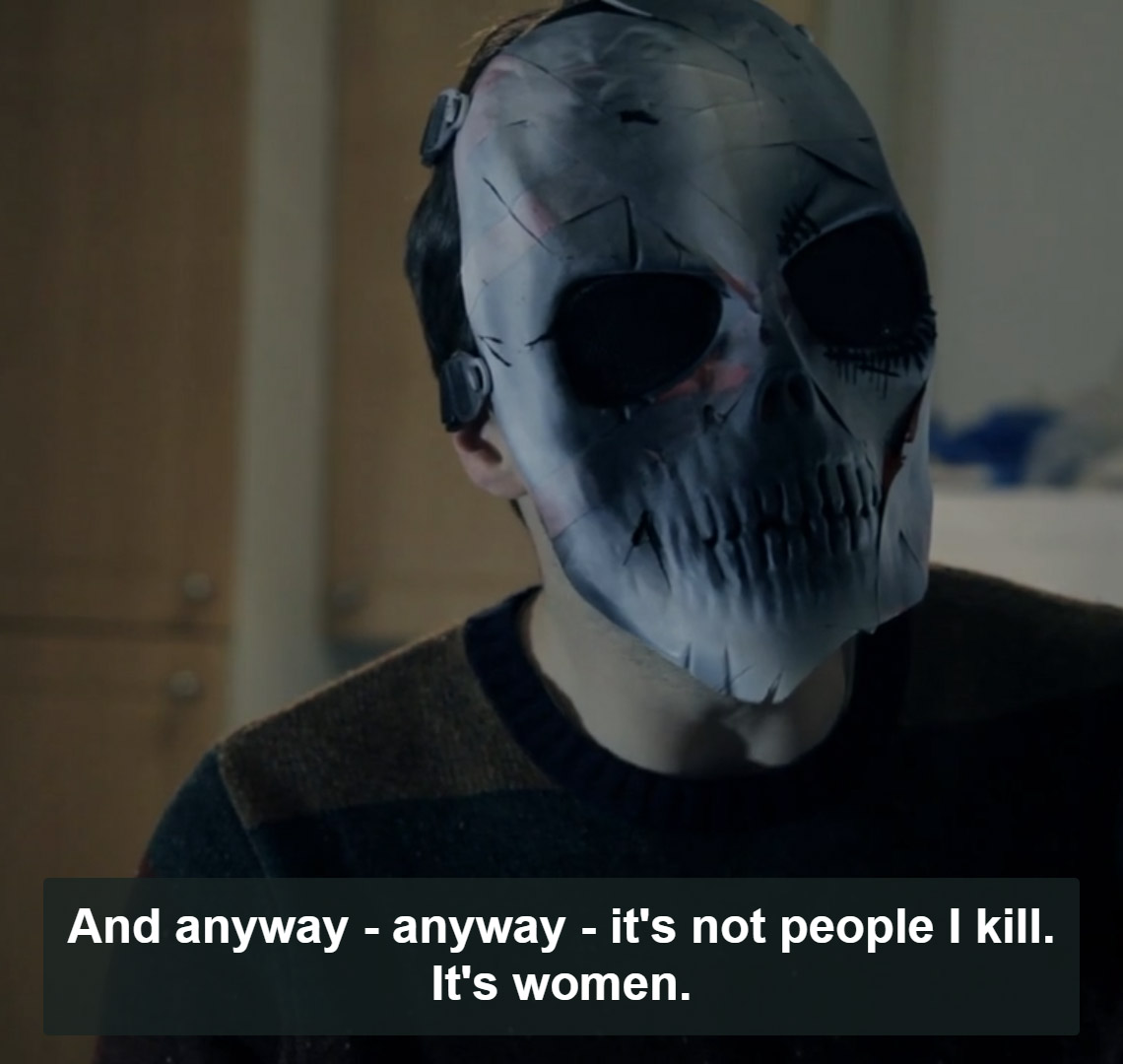

The aforementioned The House of Him is a good example. The movie could not be a more obvious propaganda if it were a Salon article, and is a generalizing condemnation of men written and directed by, of course, a man:

On top of that, it’s badly directed and edited, with scenes lacking proper pacing, and badly shot, the way your uncle played with the zoom button when filming that wedding the other day. The movie was shot on an insanely low budget by a first time director, but even that is not an excuse for some of the amateur hour we get to experience.

And yet there is something about the ending and there’s this enticing freshness to a few scenes that while I deeply disagree with the movie’s (muddy) message and execution, I do not regret watching it – on the contrary. It’s a movie I will probably still remember when a thousand others vanish from the memory.

So there can be value even in social messages as subtle as crawling over a sea of rusty nails…

…but no, that’s not something we need to concern ourselves with when we talk about Her Story. No matter how furiously you dig, no matter how hard you try to prove it, the game is not a propaganda for anything else but great writing and design.

Or, I could actually go one step further, and note that I have seen some people accusing Her Story of being “not a game” and a “feminist propaganda” without playing the game, and some other people accusing Her Story of being “anti-women”, “problematic”, “perpetuating harmful tropes” and “dodging the opportunity to say anything about women’s real experiences” after playing the game.

All right, so Her Story was not made to support a cause. But is it a game?

To answer that, first we need to understand the way Her Story works, of course.

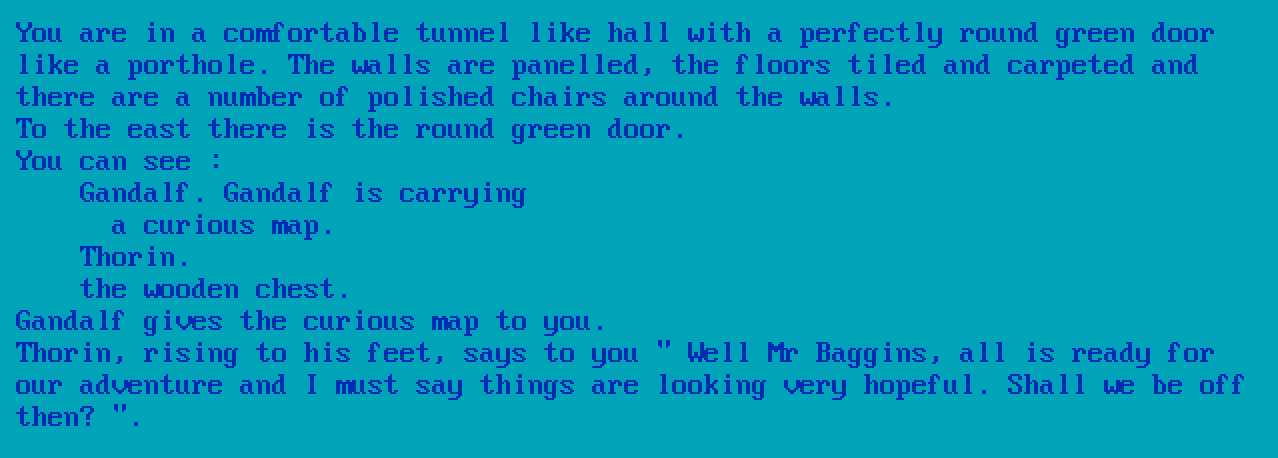

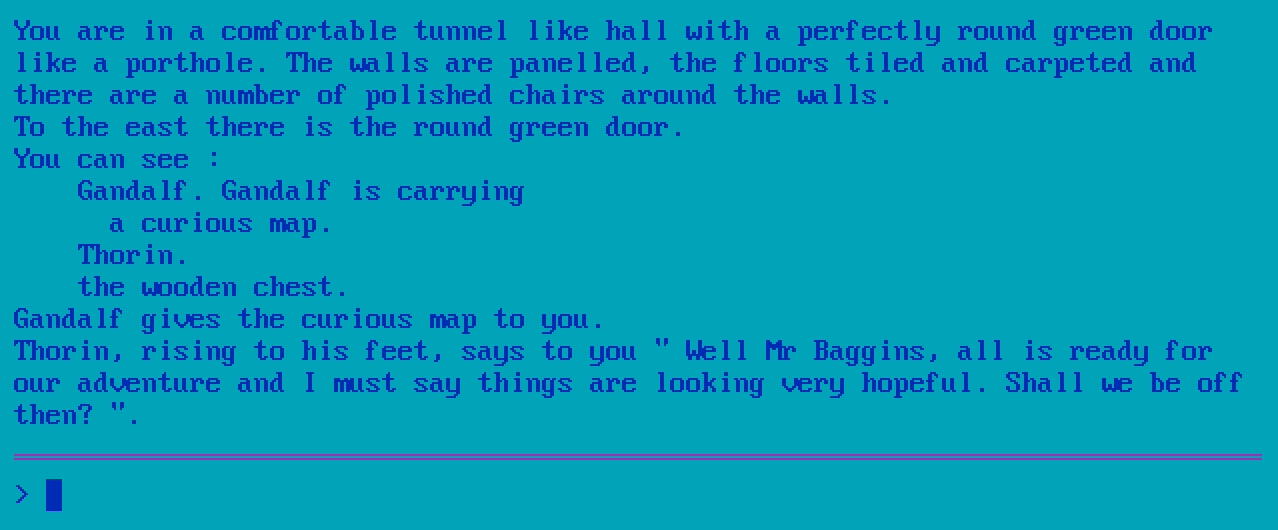

This is what every medium except for video games is:

This is what video games are:

That blinking cursor — just imagine it’s blinking — is the promise only video games can offer.

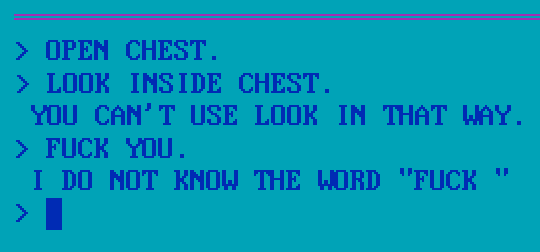

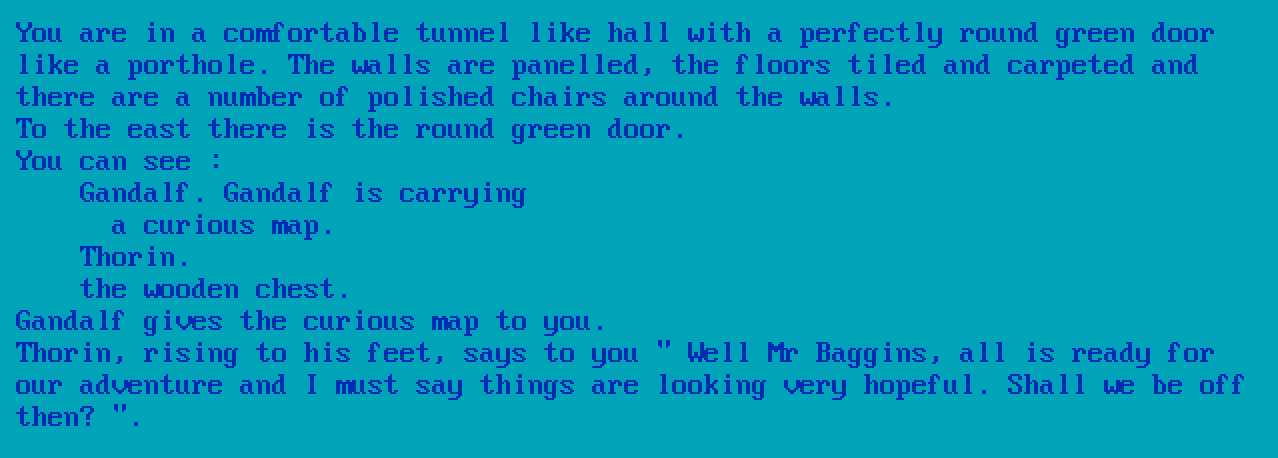

Interactive fiction, also known under the plebeian term of text adventure games, offers the freedom unlike any other type of game. The blinking cursor tells you that you can do anything. Type in whatever you want, do whatever you want.

Of course, without fail it quickly turns that’s not really true.

The reason is obvious. No creator can anticipate the player’s every move. We don’t even have digital translators that can perfectly tell in French what I said in English, let alone a database of responses to every human action possible.

This is one of the reasons why text adventures died. They promised you the world, but in reality forced the players to struggle with the most basic of actions.

The paradox is that it’s the severely restricting games like Doom that feel liberating and offer a proper service of the player agency, not text adventures. In those games, you can do anything! …just within the easily graspable internal constraints of the world.

What impressed me about Her Story is how it is a game with the blinking cursor, but one in which typing in the wrong word feels natural and is actually an integral part of the experience.

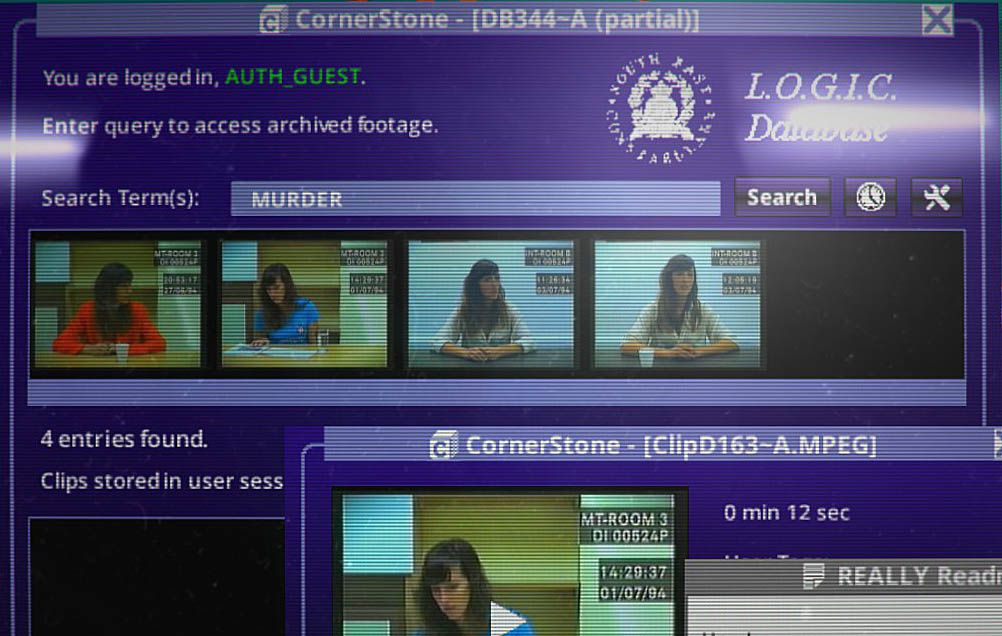

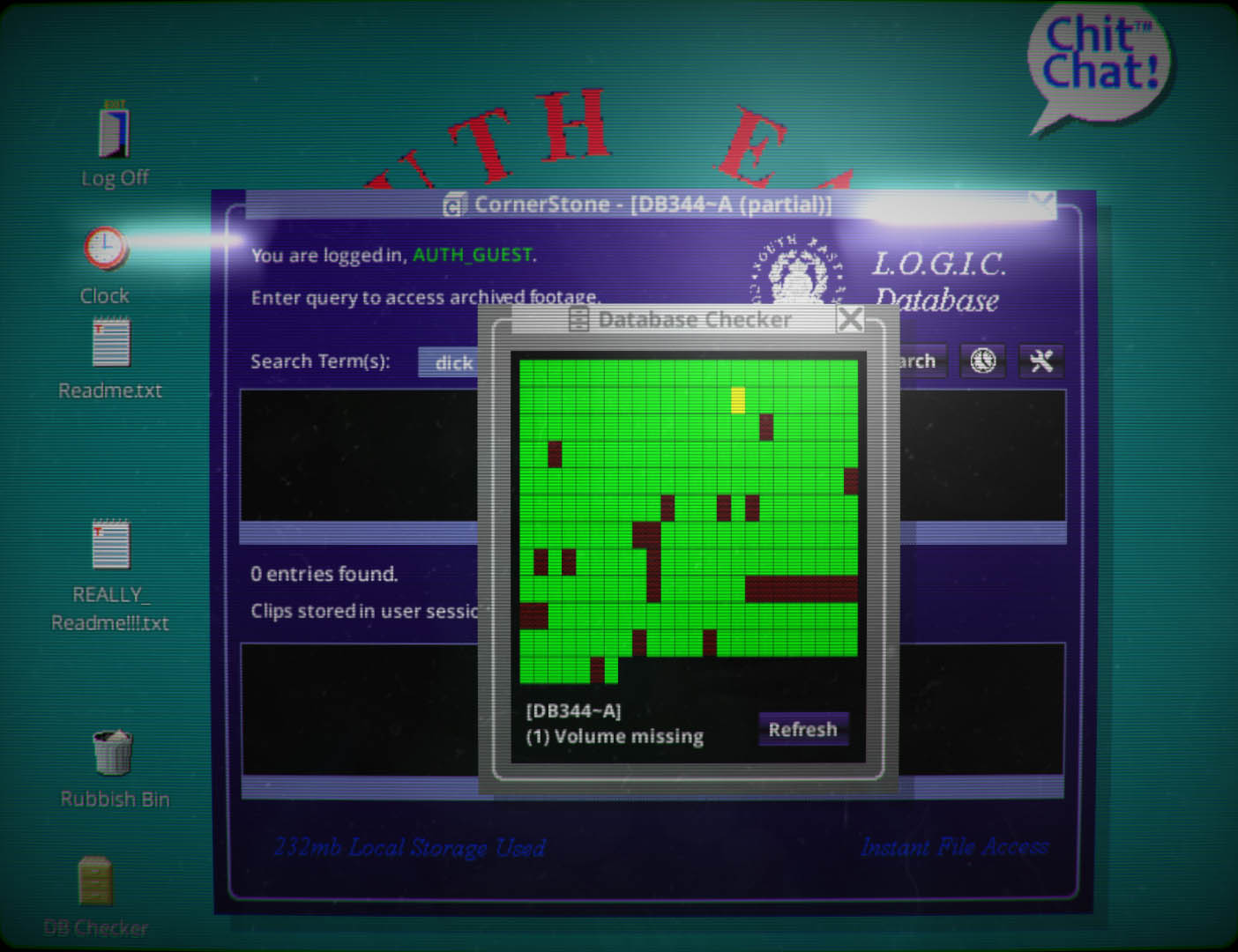

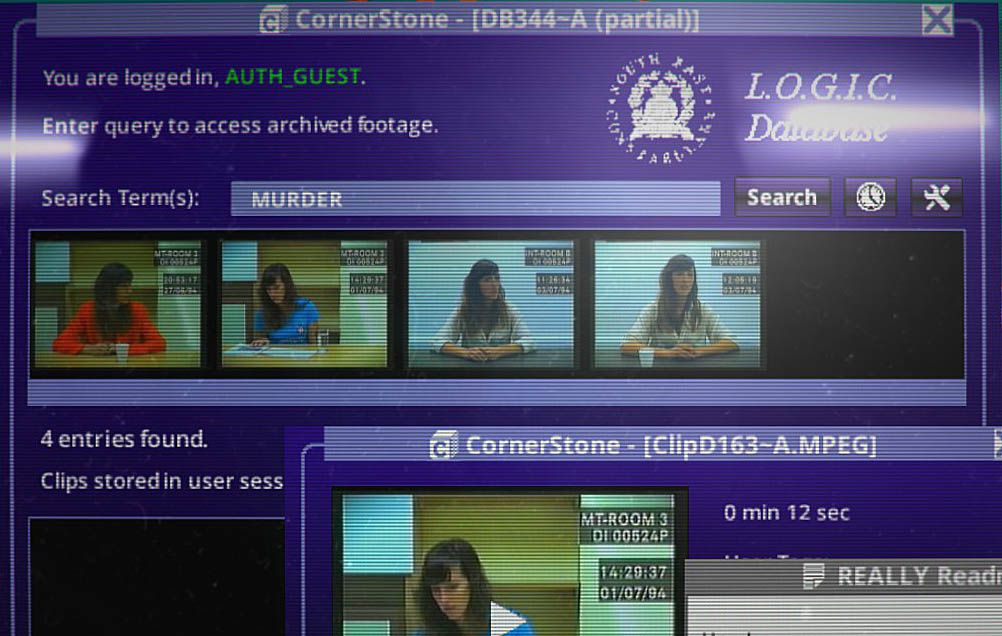

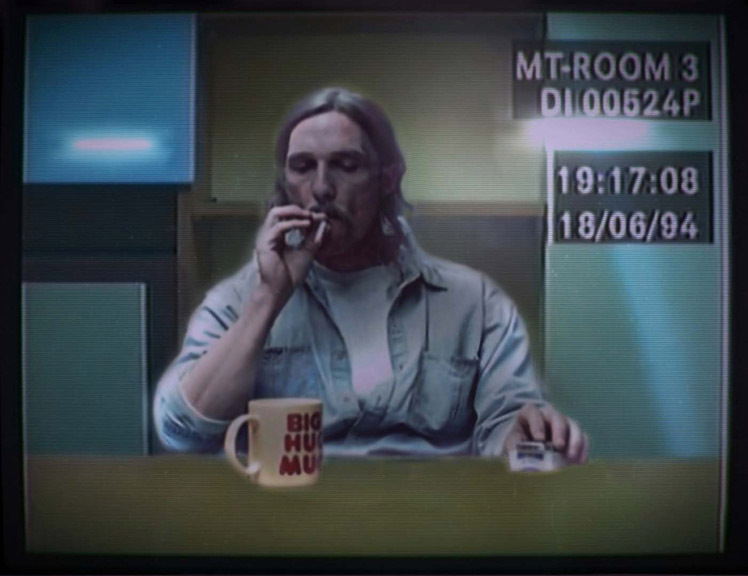

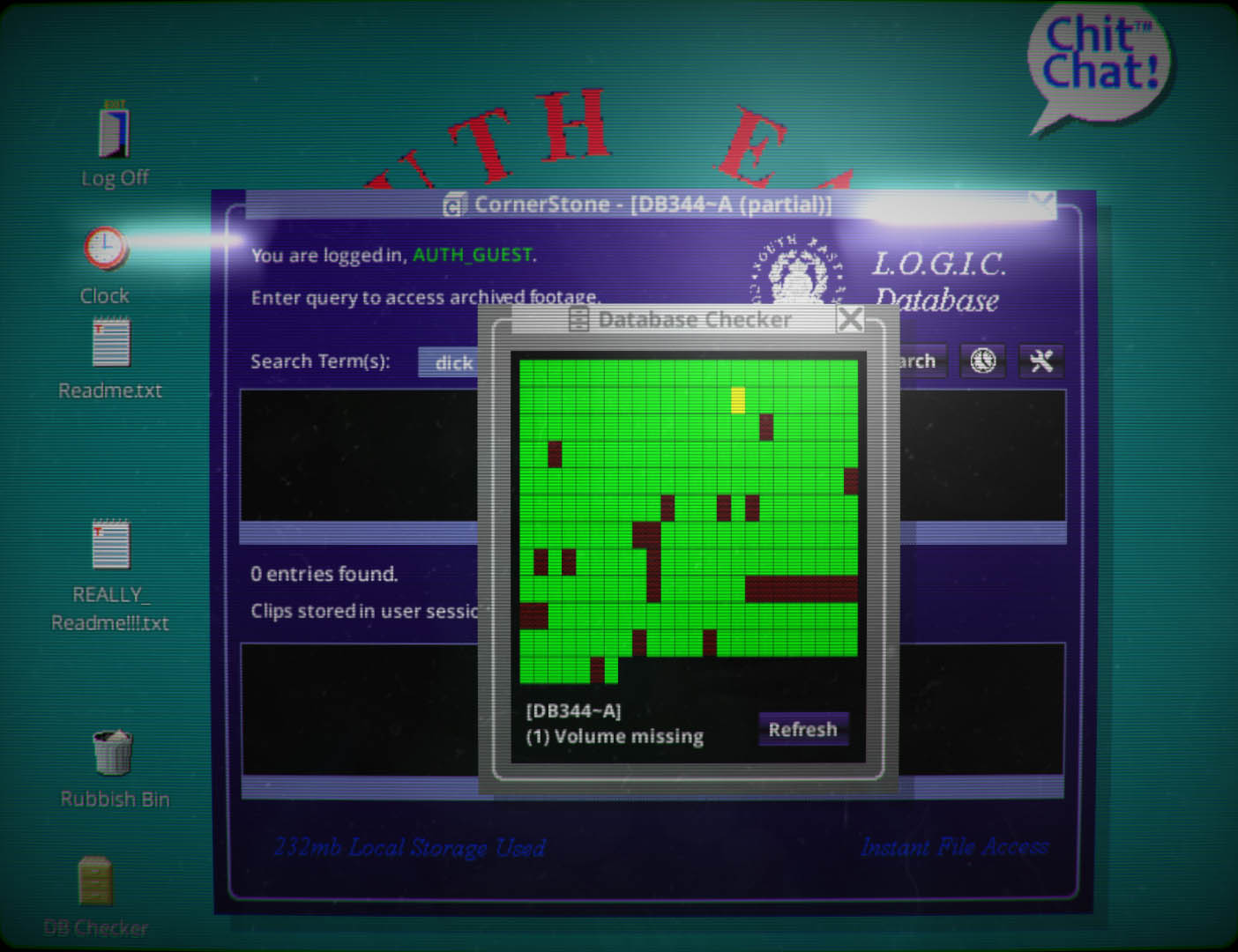

The core of the game is watching short video clips, fragments of a woman’s testimony. Then, if a word or phrase grabs your attention, you type it into the prompter and hope that some other, previously unseen clips used the same word or phrase as well and thus will now be revealed.

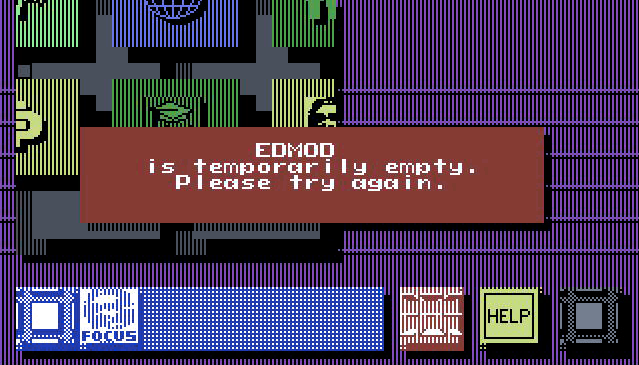

(This is not really a spoiler, that is how the game launches)

(This is not really a spoiler, that is how the game launches)

A simple and fake – as in: it’s not in the game, I made it up, so it’s not a spoiler – example:

1. You watch a clip in which a woman talks about a suspicious text message she accidentally found on her husband’s phone. It made her sad and angry. End of clip.

2. Do you wonder if anything else ever made her angry? Type in “angry” and see what happens. Or maybe you want to learn more about the text message itself? Type in “message” or narrow it down to “text message” and see if any other parts of the woman’s testimony feature the phrase.

3. Bingo! One other clip features the “text message”, and is now revealed. In this clip the woman says that the message was about a secret meeting, and it was from a woman named Mary.

4. Type in “Mary”… Hmm, nothing. Let’s try “meeting”…

Such binary success/failure gameplay results in dopamine inducing joy.

Multiple experiments showed – here’s one with monkeys – that we get a stronger dopamine hit when a reward for our actions is of “reward or nothing” type, rather than of “always some kind of reward” type.

We see this in video games, too, of course. That is the reasons why some barrels you destroy in Diablo 3 have no reward in them at all.

With Her Story, it’s the same thing. Whether the word or the phrase you type into the game’s fictional computer brings results or not, each entry feels like an exciting adventure and gets you in that famous “just one more try” mood.

If you type in the right word and discover a new video, it’s obviously exciting. You learn new things and some things get explained but the plot thickens and the mystery grows. And it gets better: when you revisit older, previously discovered clips after some of the revelations, you then see them in a completely different light.

If you type in the wrong word, unlike in the old text adventures, you’re not angry that the game refuses to offer any reward. Simply, that word did not appear in the testimony, or you already found all occurrences of the word. You get it, it makes sense.

But that’s not all. Typing in the wrong word brings out the inner detective in you. When you feel that there’s more to the sub-story than meets the eye, you start digging and attacking the problem from a different angle. So maybe you typed in the “meeting” but, just as it was the case with “Mary”, it brought no new results. How about “secret”, or “lover”, then?

And that is how the game gets you hooked. The dopamine-inducing uncertainty of reward is a strong motivator for the players to keep digging.

You might have noticed that a lot of Her Story happens in your head. The core gameplay mechanics might be deceptively simple, but the experience is nothing but. It’s a mind puzzle of the best sort, one in which your brain tries to find the meaning of information and the connection between various information streams.

It’s basically one of the best simulations of a Hollywood detective I have ever seen in a video game. That scene in a movie where the detective stands in front of the board filled with the murder timeline, crime scene photos and a map full of pinheads, waiting for the a-ha! moment? That’s Her Story. You build the board, and slowly reveal the truth through a series of a-has.

And what a truth that is. Just when you think you have it all figured out, a new piece of information destroys the narrative you put in your head. But then another piece turns it all head over heels again. It is a really good mystery by the genre’s standards in any medium.

All right, okay, but is it really a game?!

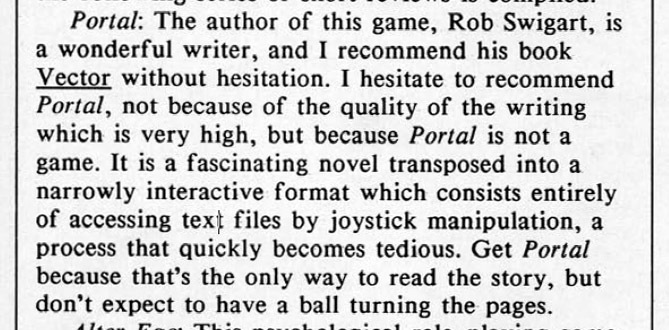

Yes, let’s talk about it more, that discussion is only a couple of decades old:

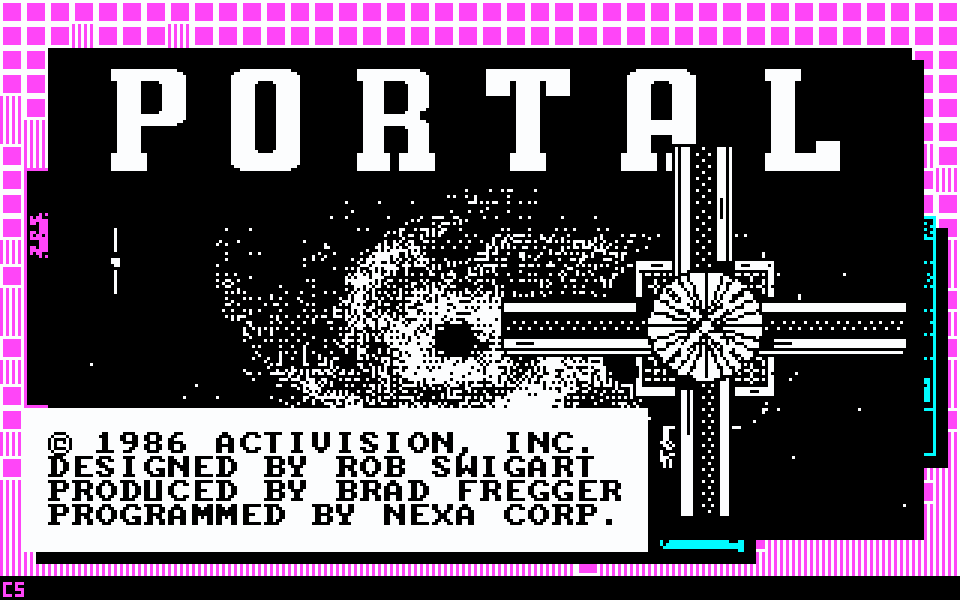

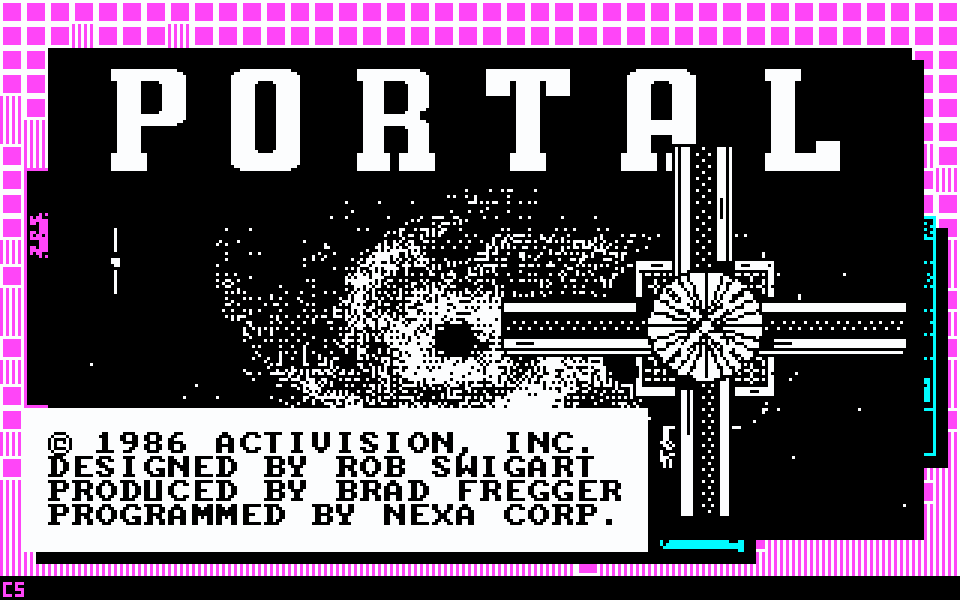

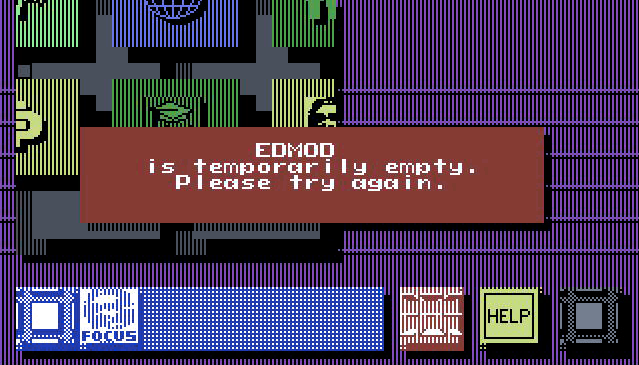

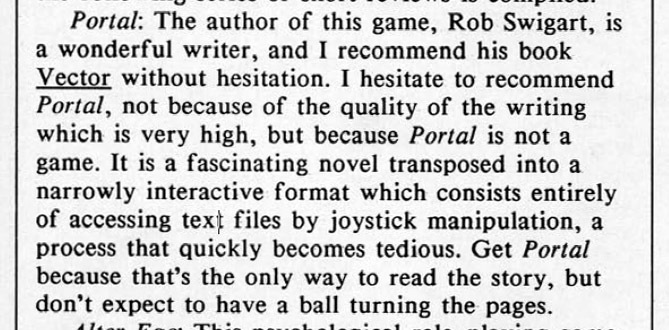

(CGW, June 1987, the review of Portal)

(CGW, June 1987, the review of Portal)

I feel like the conflict between ludofundamentalists and the rest of the world exists only because the former desperately hold onto the outdated definition of what a game is. They want conflict, they want the win condition, they want challenge and failure.

But think about the word “picture”.

The etymology is “from Middle English pycture, from Old French picture, from Latin pictūra (“the art of painting, a painting”), from pingō (“I paint”)”. Clearly, in the beginning, “picture” merely meant a painting.

But today, a photograph is also a picture. We even use the “picture” word to informally describe a movie.

It’s exactly the same with video games. Maybe originally a game did mean whatever ludo-fundamentalists want it to mean. But we left that definition behind a long, long time ago. People believe that experiments like Proteus or Dear Esther are the children of the last few years, while in reality games went beyond win/lose states decades ago.

Today, a video game is basically any kind of interactive entertainment. Even the hardcore ludologists like Jesper Juul changed their mind and accepted this…

…and I see no reason why we all should not.

There are wiser ways to spend your time and energy than to argue that a photograph is not a picture. Stop saying “it’s not a game”, and start saying “it’s not my kind of game”.

And people… Because games you might not like exist, it does not mean what you like will stop being produced. As long as there’s enough people like you enjoying certain types of games, developers will develop.

Having said all that, here’s the kicker: Her Story is a game even if you use the old school, ancient, ludo-fundamentalist definition of a game.

Mindless interaction will not get you anywhere in Her Story (challenge). You have to pay attention and prove you know what you’re doing (skill). There are clear game mechanics at play here, and you can either discover a new clip through your work and thus progress in the game, or fail and get stuck with no new clips (win/lose).

From the top level mechanics perspective, Her Story is no different to, say, The Secret of the Monkey Island. With the exception of a certain underwater Easter Egg, the only way to fail in that game is to get stuck, which is exactly what can happen in Her Story. To progress in Monkey Island is to use the right item, and to progress in Her Story is to use the right word. In both cases there’s clear action-reaction feedback loop for the player.

Are we done here, then? No, not yet.

There is, in fact, one big difference between these two games. The final thing you do in Monkey Island gets you the ending cut-scene, and then the credits roll, voila. You know exactly what happened and why. No question is left unanswered. The story is complete.

Her Story does not offer the same luxury. “Was she guilty?” and “What really happened?” are questions Her Story does not answer directly, even if you 100% the game.

Is this “Gotcha!” moment for the ludo-fundamenalists?

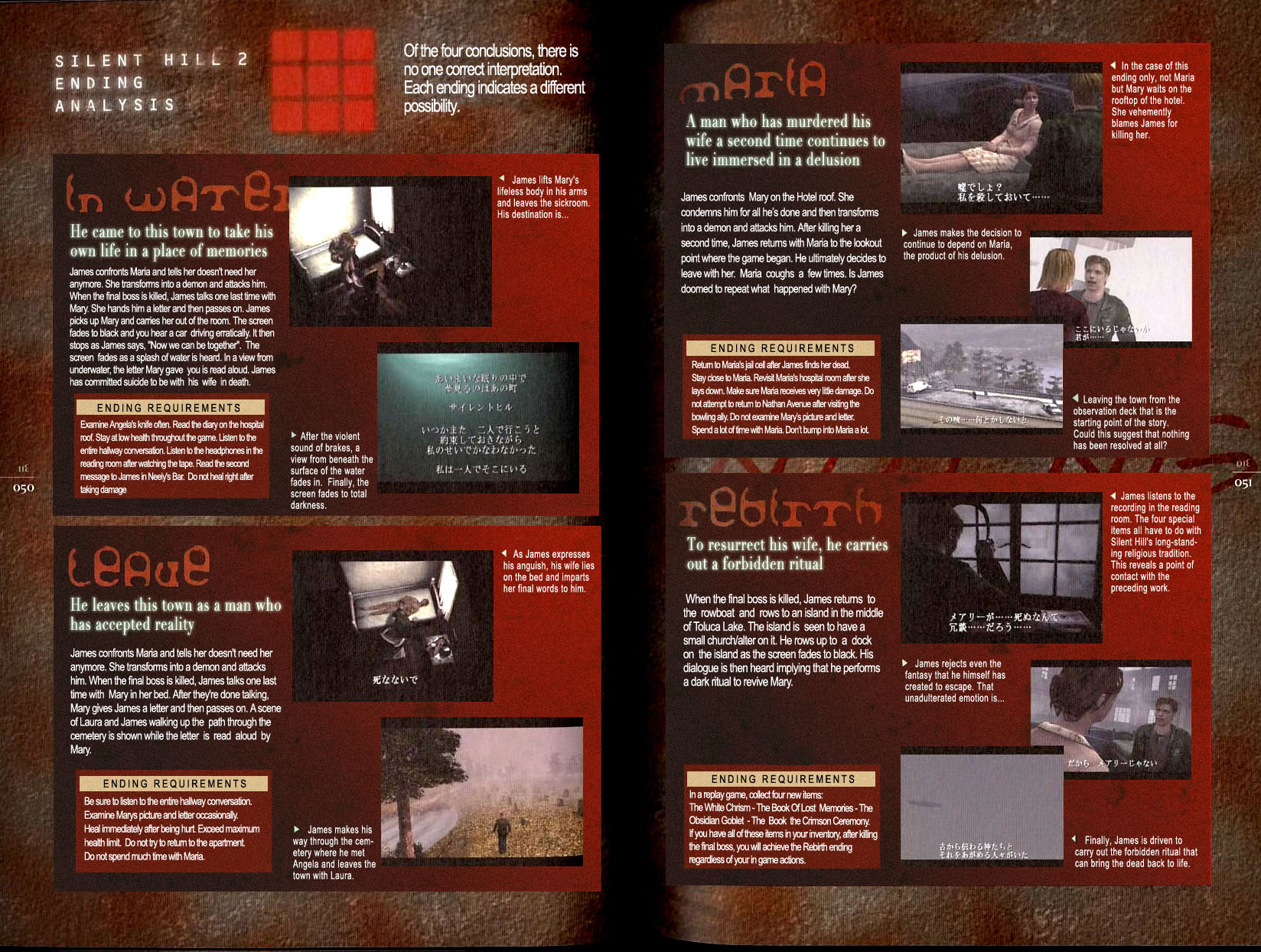

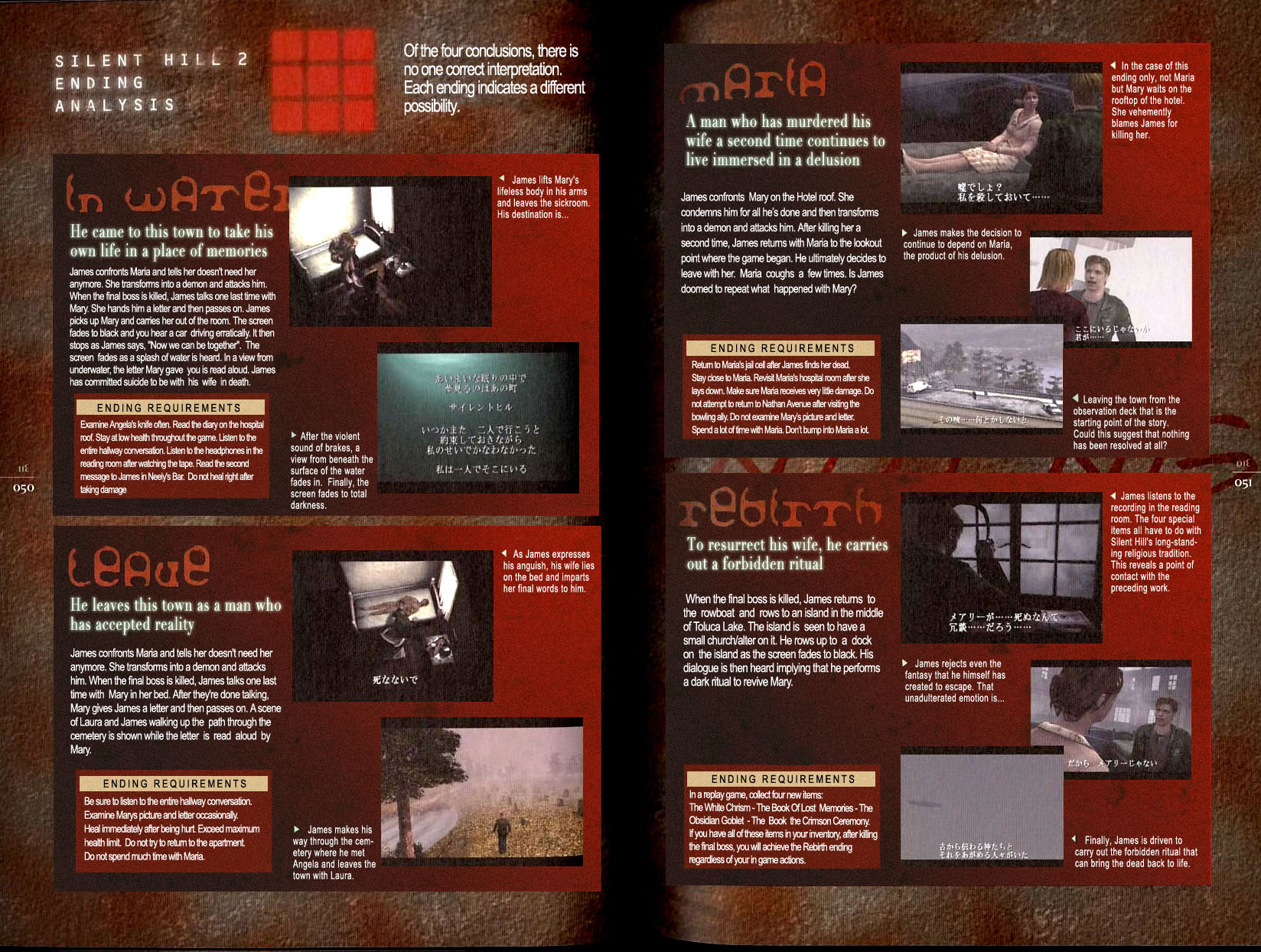

Well, if so, Silent Hill 2 is not a game either. Because that game also does not really have an ending. To be precise, it does not have a canon ending. It has six different endings. And some of them are not better or worse, they are just different.

On top of that, a few of these endings are highly enigmatic. You have to use your imagination and invent their meaning yourself.

Wait, no clear win/lose ending, and no canon ending? Blasphemy!

If you insist that Silent Hill 2 was a game after all, then its ending could be described as: the player reaches the final segment of the game, something happens, and then you see the credits roll.

Which is exactly how Her Story works, too.

Closure or game-announced ending is not sine qua non of video games anyway. What exactly is the ending of The Sims or Flappy Bird? Something you create in your head, the goal you set yourself? That’s actually less than what Her Story offers.

It’s worth noting at this point that the lack of game-acknowledged closure – i.e. there is an ending to Her Story, but whether the case is closed or not is up to you – is a proper simulation of the detective work. The real life often does not offer the ding-dong congratulatory reassurance that what you’ve done was right.

The only other game I know that attempted similar approach as Her Story was Sherlock Holmes: Crimes & Punishments (2014). You could get the facts wrong, miss a clue, and arrest a wrong person — and they might even lose their life because of your mistake. The creators did not go all the way – “a final case screen allows you to “spoil” the answer or return and modify your conclusions” – but at least there’s an option to role-play as if the game was unaware of the proper solutions.

And that’s a great way to make a detective game. I very much disliked the Murdered: Soul Suspect’s approach that sucked the life out of its mystery by telling me I found “X/Y clues” at a murder scene.

Anyway, to sum it all up, yes, Her Story is a video game by any definition of the word.

Actually, the real problem with Her Story is that it’s too video game for its own good. When you think about it, the game simply makes no sense. Elements of it exist exclusively to provide a challenge, but are too abstract and offer no justification and reality anchors of any sort.

Some gamisms become transparent to us in time. It makes no sense that our health auto-regenerates in a WW2 shooter or that enemies rarely run out of ammo. But we are so used to these features that we no longer even notice them.

Her Story’s gamisms, however, are unique to that game, and that makes them stand out and negatively affect the immersion.

It’s not just that we notice them, though. It’s also that they look like they would not be impossible to fix.

The best example I can give is the fact that the computer you use to play the videos has the search results limited to the first five clips found. Why such an artificial limit?

Because video games, of course. Must have dat challenge.

Now, I do understand why such a solution was used. Unlimited search with * would just list all clips and there would be no game, you’d just watch a two hours long multi-clip video. It would be an equivalent of godmode in Dark Souls.

Increasing the limit would not be a good solution either. If a significant number of clips popped up in the search result, that would shorten the game and, more importantly, de-focus your investigation.

So, the limit itself is a good idea. It’s just not wrapped up in any reasonable explanation that would help my suspension of disbelief.

For example, what if this was an old PC that listed all results but displayed only the first five, and the buggy search software crashed if you clicked on the “Next Five Results” arrow?

What if the clips had to be pulled from a server to a local cache/HDD small enough to handle maximum five clips only?

Or let’s you reverse psychology on the player. What if the software proudly announced an update that “Huge memory boost allows the program to buffer not one, but five clips in a single search!”?

I am sure Sam Barlow tried various things and chose simplicity. I appreciate it, but when everything else is so stylized with extreme attention to detail, the gamisms affect my experience more than I expect them to.

There are other issues, too.

Earlier I compared the game to Monkey Island, and the similarities go beyond the top level structure. Text and graphic adventures suffer from “when I am stuck, I try everything on everything” syndrome, and Her Story is no different.

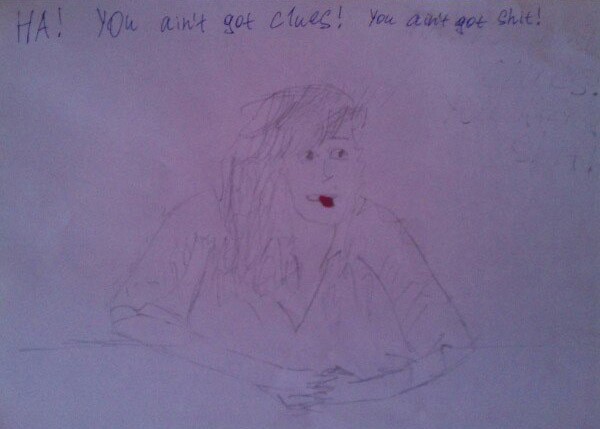

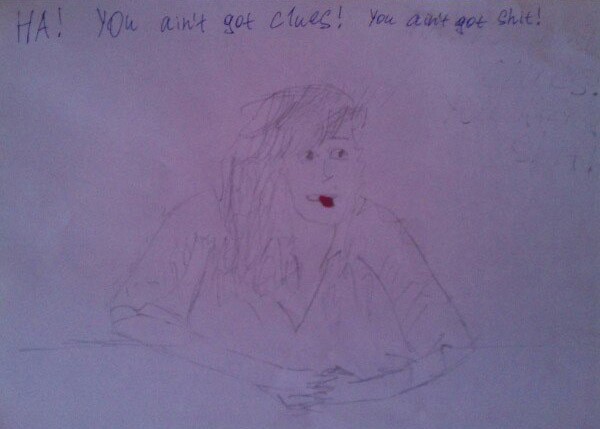

Incredible Her Story fan art captures the feeling of options exhausted.

Incredible Her Story fan art captures the feeling of options exhausted.

Even if you take notes – and you want to take notes – it is very likely that you will run out of words and phrases to search for, and you will start throwing random stuff at the game, hoping some of that will trigger a new clip. And it will.

What is frustrating is not that the game is unfair with its choice of words. It is fair, actually. When you run out of words and find a new clip through some random popular English word you never used before, you realize you could have figured out the clip properly, through deduction or observation.

Also, this “maybe some of it will stick” is actually, I guess, a part of regular investigation process. Real life detectives run out of ideas and try random angles too.

The frustrating part is that a few changes to the core design would make the experience that much more pleasant and focused. For example, there is a database of clips, ordered chronologically, with clips tagged either as watched or unwatched. But you cannot launch any discovered (i.e. previously watched) clips (e.g #19) – or, even better, a chronological series of these (e.g. #19-23) – from the database for reasons unclear to me. Allowing that would not break the game at all, but would make the hunt for words and unseen clips much more reasonable.

(This is what I was able to achieve without cheating.)

(This is what I was able to achieve without cheating.)

Luckily, these few false notes in Her Story were unable to ruin the entirety of its sweet melody for me. The pleasure that Her Story offers is strong enough to nearly silence the game’s issues. My musings here are more of a design analysis than a warning.

The title of this blog post is “What Her Story Tells Us About the Current State of Video Games”. I talked about the sociopolitics in the opening paragraphs, and I talked about the definition of a video game and how it expanded throughout the years – but none of these things are the reason behind the title.

That reason is: when I played Her Story, I felt excitement and joy, but I also felt sadness. Her Story made me realize that games could use a good kick in the ass.

Twenty years ago, a game like Her Story would just be a fun game (note I am talking about the gameplay side of things, not the story), one of many unpredictable, auteur creations. Today, it’s something special, something unique. So special and unique that this one man’s little indie game became Gamespot’s Game of the Month.

Thirty years ago, when you bought a new game, a surprise was expected. Before the birth of conventions and genres, before creators consciously or subconsciously limited their creations to something already established and easily definable, all they cared about was if their game was interesting. They just tried their best to make sure their work was something fresh, something unique.

That rarely happens today.

Her Story made me feel like I was back in the 1980s not because it uses Full Motion Video, but because it dares to be truly different and hard to define. Back then, even a game’s title ignited the imagination. Does not Tír na nÓg look enticing? What’s Nonterraqueous? What adventures await in The Great Escape?

Today, we get Warframe, Warpath, Warhawk, Warfighter, Warzone, Warface, and Wargame. Or Battlefield, Battlecry, Battleborn, and Battlefront.

It’s not the case of grandpa telling you that “today’s music is horrible”. It’s grandpa telling you “today’s music is excellent, it is just not surprising anymore”.

Of course, I am sure we could find some counter-examples: a cliché 1985 game or a fresh 2010 experience. But I still believe that, in general, something is amiss in today’s world of video games. Pixel art is everywhere, games that would be forgotten on Commodore 64 a week after release get Game of the Year awards, the most successful Kickstarter pitches are all sequels or “spiritual successors”, and Steam is flooded with rogue-likes and twin-sticks.

Actually, what is happening in the world of games is even odder than the rehash era we live in now, with X-Files on TV and Jurassic Park in cinemas. Whenever I analyze new games along with Michal, one of studio owners, we often laugh that gamers today are excited about things that were considered standard three decades ago. High difficulty games are applauded as ground-breaking, and the lack of a tutorial is revolutionary.

It is not all doom and gloom, of course. After all, you are reading a big blog post about a unique, surprising experience I just had with Her Story. Even if the idea is not totally brand new (what Sam Barlow acknowledges, of course, citing the fascinating Portal as one of his inspirations)…

…the execution was fresh enough for me to enjoy the game as if I have never seen anything like this before.

It’s worth adding, I believe, that the uniqueness of Her Story is not limited to the game’s top level idea. Her Story is ultimately a very PC game, and by PC I mean Personal Computer. Sure, it’s been released on touch devices as well, but I cannot imagine the same comfort of playing as we get with the good old mouse and keyboard. For the game to be released on consoles (chances of that are close to zero), it would have to undergo a serious redesign. I applaud Sam for the risk he took by making the game that is nearly un-portable.

Her Story is a mystery drama, not a comedy, but it did bring a big smile to my face. This little thing – the most literal video game ever – reminded me of the potential of our beloved medium, and that video games can be pretty great.

I’m sure it’s not the last game that will surprise me. I just hope its success – 100K copies sold in a month, so can we please stop wondering if gamers appreciate “art games”? – will make other creators notice the value in being different and unpredictable. Her Story has a great chance of being this influencer, especially with its unexpectedly low price.

On a personal note, the game is close to my heart not just because it has that fresh smell. As our The Vanishing of Ethan Carter, it’s an ode to stories, and even the last words spoken in both games are eerily similar, even if of a different shade of hope.

In this piece, I talked about the game from a game designer’s perspective. But I am also a gamer. I have written a detailed analysis of Her Story’s plot, and tried to solve the mystery of Simon Smith’s death once and for all. Do not read this until you have finished Her Story, but if you have, join the investigation here.

(This is not really a spoiler, that is how the game launches)

(This is not really a spoiler, that is how the game launches)

(CGW, June 1987, the review of Portal)

(CGW, June 1987, the review of Portal)

Incredible Her Story fan art captures the feeling of options exhausted.

Incredible Her Story fan art captures the feeling of options exhausted. (This is what I was able to achieve without cheating.)

(This is what I was able to achieve without cheating.)