(This is an archived old post from the previous version of the page.)

The puzzling advice I am getting when I talk about our first game? „Tell people what you want, tell them your game is ambitious, risky, uncensored – whatever. Just don’t mention that it’s short.”

“But why? It’s not like we’re going to ask the full price for it!”

“Doesn’t matter. Just …don’t draw attention to the fact that it’s not thirty hours”.

Screw it. I’m telling you right here, right now, that our game will be short. I don’t know if that means an hour or five, and if it’s going to have a fantastic replay value or not. It’s still being designed.

But I know we don’t want to make a long game just for the sake of it being long. And yes, we’re a small studio, so we could not make a big AAA game even if we wanted to. But in the future, if we become bigger, we’d rather have five smaller games in development than a single big one.

Why the hell are games long in the first place?

Two reasons.

The first one is the “value for money”.

Creators are fighting a war. Every day they kill themselves to make sure that the customer feels the “value for money”. “Yes, I pay a lot, but I get tons of content and hours of entertainment”.

Every year we get more and more of the “value for money”. Compare vinyls to CDs. Which offer bonus songs, remixes, and unplugged or live version? Compare VHS tapes to DVDs or Blurays. Which feature interviews, documentaries, and deleted scenes?

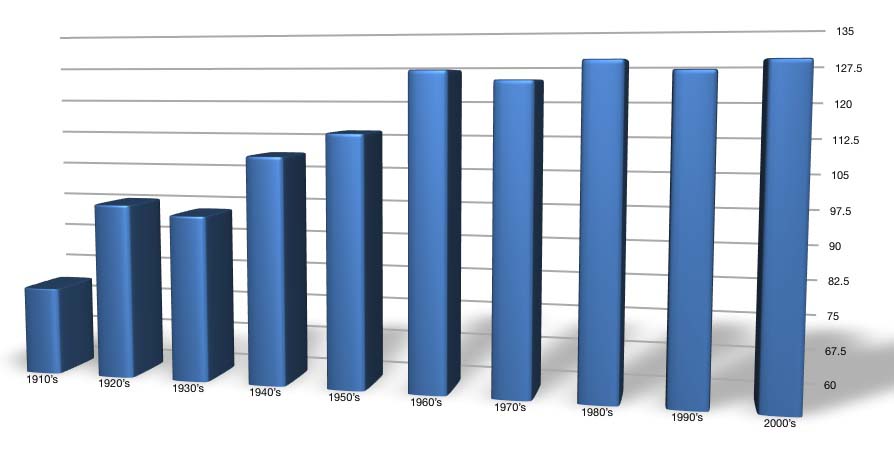

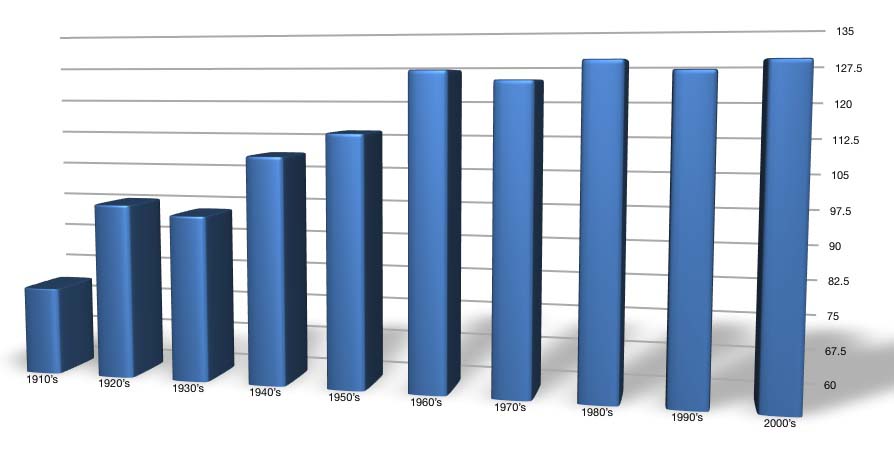

It’s really not just a question of technology. You could put movie extras on a VHS tape just fine. It’s the “value for money” war I mentioned. Just look how the average length of a movie increased in the last century – and that’s before “The Hobbit”:

And it’s easier with games. Creating a video game is a bit like creating a sitcom: once you have your “Friends” and you build a set, almost all you need to last ten years are new dialogue lines. In the case of a game, after you figure out your tech and production pipeline and create assets, it’s easier just to repeat stuff, mixing various elements into new configurations.

Here’s a simple example: Bejeweled. Leave everything as it is, just change the background picture and voila, you can call it a new level.

Who does not love “value for money”? I know I do. I pay $60 for a game, but I get dozens, sometimes hundreds of hours of gameplay. Sometimes it means weeks spent in a different universe, like it was the case with Skyrim. Sometimes it’s just a lot of content: when I bought the latest Call of Duty, I got the campaign, Nazi Zombies and a big fat multiplayer. It was literally three games in one.

But the “value for money” has a dark side too, though. After all, that extra remix you get on a CD is not a new song, the deleted scenes on a Bluray were usually deleted for a reason, and oh my fucking God do fantasy books have to be that thick?

It’s even worse in the case of games. Even though I did get three games in one with Black Ops 2, I really didn’t care about two of them: I always play CoDs just for the campaign. I wish I could buy it separately, and pay less for it.

Or take the “grinding” that some games suffer from. It’s putting boring, artificial obstacles in the way, not because they make any sense or make the game more fun. They’re there just to triple the total playtime.

Anyway, so quite often the games are long just to give the impression of “value for money”. What’s the other reason?

A box with a game that’s fairly short and thus has a lower price (say, $15) is exactly the same size as the box for a long game with a standard price ($60). They both take the same amount of space on the shelf.

But they don’t bring the same revenue to the retailer. If the retailer gets 30% of any game sold, they get $5 for a short game, and $16 for a long game. Same shelf space, different revenue.

So the story goes like this. Retailers demanded expensive games. Gamers were ready to pay as long as there was “value”. Publishers added two and two, and they only invested in long games. Ta-dam.

What’s the problem?

The problem is the risk aversion. A big, long game requires lots of time, and a large team. Lots of time multiplied by a large team equals bazillions of dollars.

But not many people like to invest bazillions of dollars into something risky. Gamers blame publishers for “more of the same” each year, but when EA took a risk and went for Mirror’s Edge and Bulletstorm and Crysis – all highly rated games – gamers did not exactly form a queue. Meanwhile, sequels to threequels keep on selling very well.

And it’s okay. Really. I blame no one. It’s human nature to avoid risk. But if it is okay for you not to risk $60 on a new gaming franchise, it’s okay for the publishers not to risk $60 million.

The results of the risk aversion? Copycat games. Tired formulas. Slow evolution of the art.

The solution? Shorter, cheaper games which are distributed digitally.

Let’s quickly get one thing out of the way first. Do I want long games to die? Hell no. I love them. I’ve put 100+ hours into Skyrim, finished most Final Fantasies, solved all 400 Riddler challenges in Batman. And I still want more.

So no, I don’t want long games to die. It’s not like short stories should kill novels or that movies should kill TV series, right? Same with games. We can have everything.

I just want games to evolve faster, and I want more choice.

And it’s finally possible. Why?

One, the digital distribution makes the brick and mortar shops irrelevant. Apple or Amazon or Big Fish care about the total volume of shit sold, not about the shelf or cloud storage space.

Two, in the old days, making a short game was like inventing a type-writer, building it, and then writing a short story with it. It made so much more sense to use it to write a book, right? But today’s tools almost eliminate that problem. We’re getting closer and closer to having third party engines and middleware allow the creators to focus on, you know, creation, rather than on technical sorcery. The proof? For example, this.

Three, shorter, cheaper games mean we can take more creative risks. It’s so much easier to part with your hard earned money if it’s just the cost of a discounted DVD or a book.

I don’t pretend to be slinging any shocking revelations here in this blog post. The Walking Dead. To the Moon. Journey. Dear Esther. FTL. Hotline Miami. And dozens of others. They already exist. They are very successful. Thank you, gamers!

Shorter, cheaper games excite me. Not just because I have a family and a job and I love other things than games and I don’t have that much free time anymore. They excite me because I love exploring new worlds.

It’s like going to a restaurant that offers a “tasting menu”: small portions of several dishes as a single meal. Each portion is the size of a walnut, but at the end of the night not only you’re full, but you’ve also tasted so many different, amazing flavors.

Shorter, cheaper games. It’s your time.